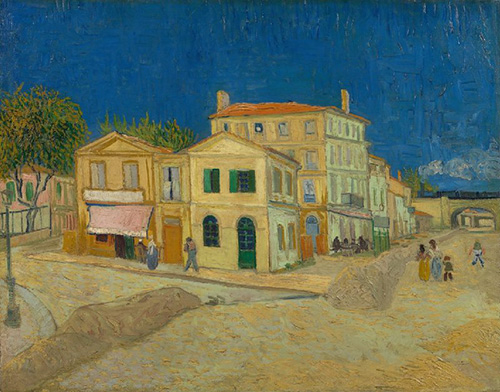

Painting a picture of research fraud

The Yellow House (The Street), Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890), Arles, September 1888, oil on canvas. Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Vincent van Gogh only sold a few paintings during his lifetime and died a poor man. After he died, his sister-in-law, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, cleverly built his reputation and created a thriving market for his paintings. Recent sales have been over USD $80 million. Vincent was both truly gifted and desperately unlucky.

Soon after his paintings started to sell, van Gogh was the victim of fraud. A German art dealer named Otto Wacker created multiple fakes and made a tidy profit until he got overconfident and put four of his forgeries in a van Gogh exhibition. Side-by-side with the real thing, his forgeries were spotted and the game was up.

Fraud happens in every area of life where there is money and prestige, and it of course happens in scientific research.

There are sadly many scientific versions of Otto Wacker, people who are willing to fake research that looks like the real thing and fools peer reviewers, but eventually smells fishy when held up to post-publication scrutiny. An example is Jan Hendrik Schön, who published multiple papers in Nature and Science that were created using made-up data. His sorry story is brilliantly told in the book Plastic Fantastic by Eugenie Reich.

Other recent examples include forgeries in super-conductivity and Alzheimer’s. These fraudsters were caught because they exhibited their work in the prominent galleries of Nature and Science. They wanted the fame and prestige of being the best, but that brings with it scrutiny from scientific sleuths (experts in spotting forgeries) and other researchers who take the work at face value and try to build on it.

There’s another larger market in fraud that mostly stays out of the limelight. Thousands, possibly hundreds of thousands, of fake papers are being churned out and published in more lowly journals. The market for this bilge is driven by researchers wanting to win promotions, qualifications, and visas. These papers don’t get the same scrutiny as the big-fakes and mostly do less damage as they may only get a handful of readers. However, some fakes have been unwittingly used in clinical guidelines, creating real harms for patients who were treated based on fabricated evidence.

The growing market in fraud risks severe harm to the reputation of science at a time when it is under attack. Interestingly, the Declaration of Helsinki was updated in 2024 to explicitly state that researchers “must never engage in research misconduct”. Whether this welcome change in wording brings some much-needed action from funders and institutions remains to be seen.

Research fraud will never be eradicated, but we can reduce its influence with some relatively simple steps, such as a greater use of open science and de-indexing journals that repeatedly publish fakes.

One response to fraud from the art world has been the Authentication in Art foundation who promote best practice in fraud detection. There is a similar clubbing together of experts in spotting research fraud, with the recent Paris declaration to fight fake science. However, it’s amazing how little money there is to work in scientific fraud given the potential reputation damage and harms to the public. Last year, the mega-publisher Elsevier made USD $4.1 billion in profit. We should be spending at least a “van Gogh” on detecting fraud, which for an $80 million dollar painting would be just 2% of Elsevier’s profits.

This article was written for the Deeble Institute for Health Policy Research, March 2025.